Part 1: Listening

Listening?⌗

The first step towards having a distributed system is for a way to make it “listen”. Ideally, your system should be able to branch out its operations by understanding the context in which it is invoked. This includes stuff like input/invocation arguments, communicated entities, internal state, etc. We shall start with these forms of understanding before we move on to more complex means of deducing context.

Input / Invocation Arguments, and why we need active listening⌗

I wouldn’t characterize this as “listening” per se, but rather “knowing in what context one spawns”. We shall talk about this later, when we need to handle multiple “listeners”, but for now, let’s focus on the actual listening that takes place.

Listening, for me, is the ability for a component to process information that is intended to be used by it in real-time. This would not require the component to rerun, or retrigger, when it needs to move on from the previous information. Let me explain with a simple python example.

from sys import argv

def main():

if len(argv) != 2:

print("No input file")

elif argv[1] != "Hello":

print(f"Not a greeting {argv[1]}")

else:

print("Hello!")

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

Here, if I were to run this with a single argument, and then decided to try the function out with another, I must always trigger a new run of the program. This becomes a problem if I have external, rate-limited dependencies that I would want to keep common for multiple invocations of the program, or maybe even a complex setup process. There’s a lot of wasted time and potentially wasted work. Is there a way for the program to do something as follows?

Well, that’s where the act of “active listening” comes in. To do this, we shall use the concept of a socket. A socket is a simple endpoint for two-way comms, giving it an option to listen, and “speak” (We shall visit this ability in a while). In most operating systems, it is treated similar to a file, which means we can read from it, and write into it as well. Within the kernel, a “socket table” is stored, and it, in turn, returns a file descriptor for the process requesting it.

A socket has a send buffer, and a receive buffer. Until the listener actually reads the data, it is stored in the “receive” buffer. Similarly, until the underlying protocol confirms that the data has been successfully sent to the receiving party, the send buffer holds the data to be sent.

So, how would a listener read it? Usually, languages provide read() functions

along with of their listen() functions, which allow the program to branch off

the main logic and handle them asynchronously. Let’s revisit that topic later,

when we explore synchronization and asynchronous functions. For now, all we need

to know is:

An asynchronous function is one that does not block the process while it waits for a potentially time-consuming operation. It triggers the task and immediately returns control to the caller, giving the function the need to take control only when there is something new for it to process.

Once the listener gets some input, it shall read the buffer, and then process that information accordingly, asynchronously, ensuring that long-running requests do not block other requests.

For that, let’s start out with an example.

Rust⌗

I started off with Rust because it guarantees memory safety, speed, and a strong “you better know what you’re doing”. It prevents data races, forces you to “borrow” the memory you want to use, and ensures that you don’t end up working on a destroyed object ever. You know, stuff that is necessary when you have a metric ton of processes that want to use a combined pool of memory.

Getting started with Rust⌗

If this is your first time ever trying out Rust, please check out the install documentation here. There is also a quick tutorial here.

Getting started with a practical example⌗

For my practical example, we shall use tokio for building the backbone of our listener. We shall build a simple TCP server, which can read what we sent and simply echo it back with some additional information. In future articles, we shall explore sending specific requests and parsing them.

So, here goes.

1. Starting a new project⌗

Let’s create a new project with cargo.

$ cargo new simple_socket_comm

You should see a folder created with the new project. It also contains a src/

folder with a simple hello world application. Let’s get started on replacing it

with an actual application.

Getting dependencies⌗

Since tokio is an external “crate” (library), we will need to declare it

explicitly so that your build systems know that it should be downloaded.

In your cargo.toml, add the following under your [dependencies] menu:

tokio = { version = "1", features = ["full"] }

If you have rust-analyzer installed (highly recommended), it should start

getting this dependency and indexing your project.

The actual code⌗

The goal of our project is as follows:

- Listen to data at a port

- Accept connections in the port and keep reading data in the socket that the connection sends

- Reply to the sender the same message with a simple prefix.

Step 0: Setup the tokio runtime⌗

We shall define the tokio runtime as follows. Replace your main() function

to the following:

#[tokio::main]

async fn main() -> std::io::Result<()> {

// TODO

}

By defining main() as async, we can await functions inside main() without

having to explicitly define a new tokio runtime. The #[tokio::main] macro

adds a bit of convenience and avoids us having to write more boilerplate code.

Asynchronous functions return a future, whose value can be awaited.

Step 1: Listen to data at a port⌗

We shall do this using a TcpListener from tokio. Use the dependency and

define a listener as follows:

use tokio::net::TcpListener;

async fn main() -> std::io::Result<()> {

// Bind the server to the address

let listener = TcpListener::bind("127.0.0.1:8080").await?;

println!("Server is listening on 127.0.0.1:8080");

}

The question mark(?) after await tells us:

If the action is successful: Set the future value to

listener. If not, panic and exit.

In a few cases, we will want to deal with these errors explicitly. Here, this error is serious enough to warrant a panic.

Step 2: Accept connections and keep reading data⌗

Now that we are listening at the address, we will need to accept connections to it and create a socket for us to read data from and send data to. We also need to ensure that our server can handle multiple connections and handle them concurrently.

Add the following code:

loop {

// Accept the incoming connection at the address

let (mut socket, addr) = listener.accept().await?;

println!("New connection from {}", addr);

// Spawn a new task to handle the connection

tokio::spawn(async move {

let mut buf = vec![0; 1024];

loop {

// Read data from the socket as long as it cmes

match socket.read(&mut buf).await {

Ok(0) => {

// Zero bytes implies closed connection

println!("Connection closed by {}", addr);

return;

}

Ok(_) => {

// Print the data

let data = String::from_utf8(buf.clone()).unwrap();

println!("Data: {}", data);

// Clear the buffer

buf.fill(0);

}

Err(e) => {

// Could not read from socket

eprintln!("Failed to read from socket; error = {:?}", e);

return;

}

}

}

});

}

You will also need to ensure that the necessary traits are included, which in

this case is tokio::io::AsyncReadExt, which unlocks read(). Add this to the

top of your file:

use tokio::io::AsyncReadExt;

So what does the above code block do?

The outer

loopensures that the server stays on even when all connections are closed. If not, we would end up with the server exiting after the first connection was closed.Once we get a connection, we spawn an asynchronous task to parse the value we got and do more tasks with it. Now here too - we need to handle two non-happy cases:

a. The connection was closed (

0bytes sent to the socket)b. An unknown error (which we return as an

Error)When we are able to parse the data properly, we simply print the data.

In the first unhappy case, we silently exit as the asynchronous function has

served its purpose. In the second case, we print the error and return (without

panicking, so that other invocations are not affected).

read() always returns either the number of bytes read, or an error.

Let’s go a little deeper. Why do we need to clone buf?

Well, this is rust by design. Since the String::from_utf8 returns a String

reference, it needs to always be sure that the String’s data in the heap is

valid. This means that the data that we pass to the function needs to be fully

“owned” by it, ensuring concurrent code execution may not clear or modify

the data. Thus, you know that if there is some data your function uses, there

can be no way another entity can access it (unless you set it up as such, which

we shall talk about later).

Finally, we clear the buffer (fill it with zeroes). This prevents it from having stale data when we next read for the same sender.

Step 3: Write data back to the sender⌗

Now we know that we can only write data back if we were sent non-zero bytes and were able to parse the buffer into a string. In this case, we shall return the same string with a small prefix.

Replace your Ok(_) branch with the following. The underscore argument implies

that we do not use the value anywhere in this function.

Ok(_) => {

// Echo the data back to the client with additional

// info

let data = String::from_utf8(buf.clone()).unwrap();

let returnable = format!("Returning: {}", data);

if let Err(e) = socket.write_all(

returnable.as_bytes()).await {

eprintln!(

"Failed to write to socket; error = {:?}", e);

return;

}

// Clear the buffer

buf.fill(0);

}

Now what we do here differently is, we parse the input data into the string and

then add a prefix using format!. Then we convert the string into bytes and

write the same into the socket. The write_all function returns only an error,

if any. In case we encounter it, we print the error and silently exit.

write_all also requires an additional trait which unlocks write_all(), this

is the tokio::io::AsyncWriteExt trait.

In the end, your code might look like this:

use tokio::net::TcpListener;

use tokio::io::{AsyncReadExt, AsyncWriteExt};

#[tokio::main]

async fn main() -> std::io::Result<()> {

// Bind the server to the address

let listener = TcpListener::bind("127.0.0.1:8080").await?;

println!("Server is listening on 127.0.0.1:8080");

loop {

// Accept the incoming connection at the address

let (mut socket, addr) = listener.accept().await?;

println!("New connection from {}", addr);

// Spawn a new task to handle the connection

tokio::spawn(async move {

let mut buf = vec![0; 1024];

loop {

// Read data from the socket as long as it cmes

match socket.read(&mut buf).await {

Ok(0) => {

// Zero bytes implies closed connection

println!("Connection closed by {}", addr);

return;

}

Ok(_) => {

// Echo the data back to the client with additional

// info

let data = String::from_utf8(buf.clone()).unwrap();

let returnable = format!("Returning: {}", data);

if let Err(e) = socket.write_all(

returnable.as_bytes()).await {

eprintln!(

"Failed to write to socket; error = {:?}", e);

return;

}

// Clear the buffer

buf.fill(0);

}

Err(e) => {

// Could not read from socket

eprintln!(

"Failed to read from socket; error = {:?}", e);

return;

}

}

}

});

}

}

Building and running⌗

You can build (and run in the same command) using:

$ cargo run

You may see a lot of compilation steps, and finally your program might run as follows:

$ cargo run

Finished `dev` profile [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.02s

Running `target/debug/simple_socket_comm`

Server is listening on 127.0.0.1:8080

Let’s try “talking” to the server. Run the following in another terminal:

$ nc 127.0.0.1 8080

This spawns off netcat, which helps you write data to a given address and

returns whatever the entity on the other side returns, raw. Try writing

something, and you’ll see the returned value on your client. On your

server, you will also be able to see the IP address of the nc client.

For example, on the server:

$ cargo run

Finished `dev` profile [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.02s

Running `target/debug/simple_socket_comm`

Server is listening on 127.0.0.1:8080

New connection from 127.0.0.1:55536

And on the client, note the added prefix:

$ nc 127.0.0.1 8080

Hello there

Returning: Hello there

If you want to log every request that comes in, feel free to bring back the old

println! that we had before we began writing data back to the client.

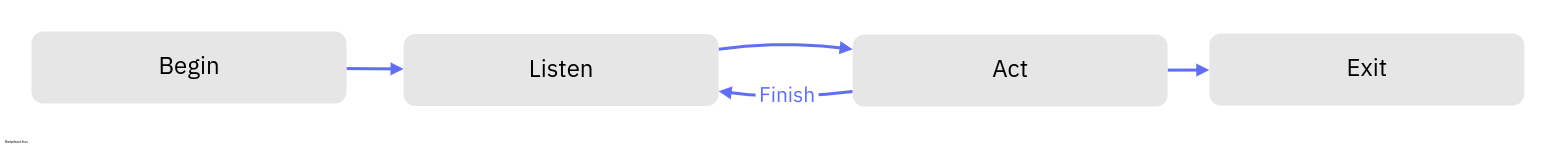

Great! We shall next try to see how we can combine both listening and speaking, and learn how we can combine both to have a truly communicative application.